Are we wrong about the age of the universe? The James Webb telescope is raising big questions.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the largest and most powerful space telescope built to date. Since it was launched in December 2021 it has provided groundbreaking insights. These include discovering the earliest and most distant known galaxies, which existed just 300 million years after the Big Bang.

Distant objects are also very ancient because it takes a long time for the light from these objects to reach telescopes. JWST has now found a number of these very early galaxies. We’re effectively looking back in time at these objects, seeing them as they looked shortly after the birth of the universe.

These observations from JWST agree with our current understanding of cosmology — the scientific discipline that aims to explain the universe — and of galaxy formation. But they also reveal aspects we didn’t expect. Many of these early galaxies shine much more brightly than we would expect given that they existed just a short time after the Big Bang.

Brighter galaxies are thought to have more stars and more mass. It was thought that much more time was needed for this level of star formation to take place. These galaxies also have actively growing black holes at their centres — a sign that these objects matured quickly after the Big Bang. So how can we explain these surprising findings? Do they break our ideas of cosmology or require a change to the age of the universe?

Scientists have been able to study these early galaxies by combining JWST’s detailed images with its powerful capabilities for spectroscopy. Spectroscopy is a method for interpreting the electromagnetic radiation that’s emitted or absorbed by objects in space. This in turn can tell you about the properties of an object.

Our understanding of cosmology and galaxy formation rests on a few fundamental ideas. One of these is the cosmological principle, which states that, on a large scale, the universe is homogeneous (the same everywhere) and isotropic (the same in all directions). Combined with Einstein’s theory of general relativity, this principle allows us to connect the evolution of the universe —- how it expands or contracts —- to its energy and mass content.

Related: The James Webb telescope has brought cosmology to a tipping point. Will it soon reveal new physics?

The standard cosmological model, known as the “Hot Big Bang” theory, includes three main components, or ingredients. One is the ordinary matter that we can see with our eyes in galaxies, stars and planets. A second ingredient is cold dark matter (CDM), slow-moving matter particles that do not emit, absorb or reflect light.

The third component is what’s known the cosmological constant (Λ, or lambda). This is linked to something called dark energy and is a way of explaining the fact that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. Together, these components form what is called the ΛCDM model of cosmology.

Dark energy makes up about 68% of the total energy content of today’s universe.

Despite not being directly observable with scientific instruments, dark matter is thought to make up most of the matter in the cosmos and comprises about 27% of the universe’s total mass and energy content.

While dark matter and dark energy remain mysterious, the ΛCDM model of cosmology is supported by a wide range of detailed observations. These include the measurement of the universe’s expansion, the cosmic microwave background, or CMB (the “afterglow” of the Big Bang) and the development of galaxies and their large-scale distribution — for example, the way that galaxies cluster together.

The ΛCDM model lays the groundwork for our understanding of how galaxies form and evolve. For example, the CMB, which was emitted about 380,000 years after the Big Bang, provides a snapshot of early fluctuations in density that occurred in the early universe. These fluctuations, particularly in dark matter, eventually developed into the structures we observe today, such as galaxies and stars.

How stars form

Galaxy formation consists of complex processes influenced by numerous different physical phenomena. Some of these mechanisms are not fully understood, such as what processes govern how gas in galaxies cools and condenses to form stars.

The effects of supernovae, stellar winds and black holes that emit significant amounts of energy (sometimes called active galactic nuclei, or AGN) can all heat or expel gas from galaxies. This in turn can boost or curtail star formation and therefore influence the growth of galaxies.

The efficiency and scale of these “feedback processes”, as well as their cumulative impact over time, are poorly understood. They are a significant source of uncertainty in mathematical models, or simulations, of galaxy formation.

Significant advances in complex numerical simulations of galaxy formation have been made over the past ten years. Insights and hints can still be gained from simpler simulations and models that relate star formation to the evolution of dark matter halos. These halos are massive, invisible structures made from dark matter that effectively anchor galaxies within them.

One of the simpler models of galaxy formation assumes that the rate at which stars form in a galaxy is directly tied to gas flowing into those galaxies. This model also proposes that the star formation rate in a galaxy is proportional to the rate at which dark matter halos grow. It assumes a fixed efficiency at converting gas into stars, regardless of cosmic time.

This “constant star formation efficiency” model is consistent with star formation increasing dramatically in the first billion years after the Big Bang. The rapid growth of dark matter halos during this period would have provided the necessary conditions for galaxies to form stars efficiently. Despite its simplicity, this model has successfully predicted a wide range of real observations, including the overall rate of star formation across cosmic time.

Secrets of the first galaxies

JWST has ushered in a new era of discovery. With its advanced instruments, the space telescope can capture both detailed images and high resolution spectra — charts showing the intensity of electromagnetic radiation emitted or absorbed by objects in the sky. For JWST, these spectra are in the near infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Studying this region is crucial for observing early galaxies whose optical light has turned into near infrared (or “redshifted”) as the universe has expanded.

Redshift describes how the wavelengths of light from galaxies become stretched as they travel. The more distant a galaxy is, the greater its redshift.

Over the past two years, JWST has identified and characterized galaxies at redshifts with values of between ten and 15. These galaxies, which formed around 200-500 million years after the Big Bang, are relatively small for galaxies (about 100 parsecs, or 3 quadrillion kilometres, across). They each consist of around 100 million stars, and form new stars at a rate of about one sun-like star per year.

While this does not sound very impressive, it implies that these systems double their content of stars within only 100 million years. For comparison, our own Milky Way galaxy takes about 25 billion years to double its stellar mass.

Early galaxy formation

The surprising findings from JWST of bright galaxies at high redshifts, or distances, could imply that these galaxies matured faster than expected after the Big Bang. This is important because it would challenge existing models of galaxy formation. The constant star-formation efficiency model described above, while effective at explaining much of what we see, struggles to account for the large number of bright and distant galaxies observed with a redshift of more than ten with a redshift of more than ten.

To address this, scientists are exploring various possibilities. These include changes to their theories of how efficiently gas is converted into stars over time. They are also reconsidering the relative importance of the feedback processes — how phenomena such as supernovae and black holes also help regulate star formation.

Some theories suggest that star formation in the early universe may have been more intense or “bursty” than previously thought, leading to the rapid growth of these early galaxies and their apparent brightness.

Others propose that different factors, such as lower amounts of galactic dust, a top-heavy distribution of star masses, or contributions from phenomena such as active black holes, could be responsible for the unexpected brightness of these early galaxies.

These explanations invoke changes to galaxy formation physics in order to explain JWST’s findings. But scientists have also been considering modifications to broad cosmological theories. For example, the abundance of early, bright galaxies could be partly explained by a change to something called the matter power spectrum. This is a way to describe density differences in the universe.

One possible mechanism for achieving this change in the matter power spectrum is a theoretical phenomenon called “early dark energy”. This is the idea that a new cosmological energy source with similarities to dark energy may have existed at early times, at a redshift of 3,000. This is before the CMB was emitted and just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

This early dark energy would have decayed rapidly after the stage of the universe’s evolution known as recombination. Intriguingly, early dark energy could also alleviate the Hubble tension — a discrepancy between different estimates of the universe’s age.

One paper published in 2023 suggested that the galaxy findings from JWST required scientists to stretch the age of the universe by several billion years.

However, other phenomena could account for the bright galaxies. Before JWST’s observations are used to invoke changes to broad ideas of cosmology, a more detailed understanding of the physical processes in galaxies is essential.

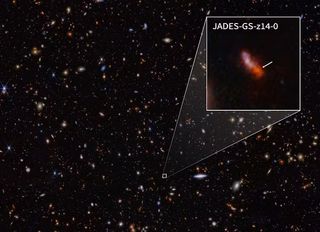

The current record holder for the most distant galaxy — identified by JWST — is called JADES-GS-z14-0. The data gathered so far indicate that these galaxies have a large diversity of different properties.

3D visualisation of galaxies observed by the JWST, including JADES-GS-z14-0.

Some galaxies show signs of hosting black holes that are emitting energy, while others seem to be consistent with hosting young, dust-free populations of stars. Because these galaxies are faint and observing them is expensive (it takes exposure times of many hours), only 20 galaxies for which the redshift is more than ten have been observed with spectroscopy to date, and it will take years to build a statistical sample.

A different angle of attack could be observations of galaxies at later cosmic times, when the universe was 1 billion to 2 billion years old (redshifts of between three and nine). JWST’s capabilities give researchers access to crucial indicators from stars and gas in these objects that can be used to constrain the overall history of galaxy formation.

Breaking the universe?

In the first year of JWST’s operation, it was claimed that some of the earliest galaxies had extremely high stellar masses (the masses of stars contained within them) and a change in cosmology was needed to accommodate bright galaxies that existed in the very early universe. They were even dubbed “universe-breaker” galaxies.

Soon after, it was clear that these galaxies do not break the universe, but their properties can be explained by a range of different phenomena. Better observational data showed that the distances to some of the objects were overestimated (which led to an overestimation of their stellar masses).

The emission of light from these galaxies can be powered by sources other than stars, such as accreting black holes. Assumptions in models or simulations can also lead to biases in the total mass of stars in these galaxies.

As JWST continues its mission, it will help scientists refine their models and answer some of the most fundamental questions about our cosmic origins. It should unlock even more secrets about the universe’s earliest days, including the puzzle of these bright, distant galaxies.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.